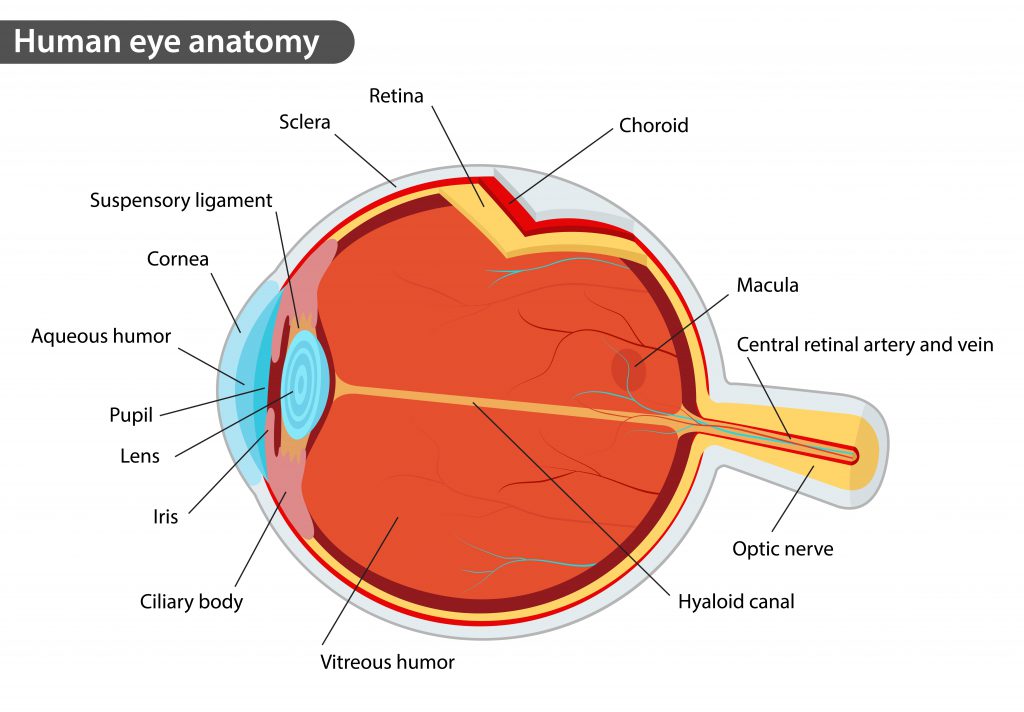

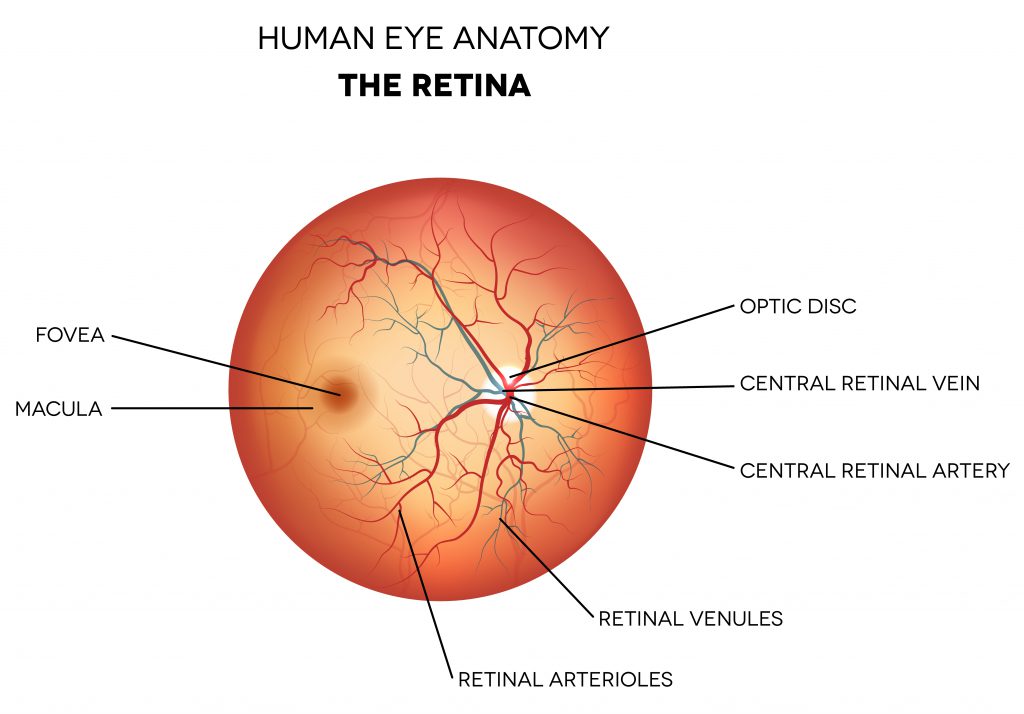

The retina is a subspecialty of ophthalmology that deals with the posterior, or back, portion of the eye (behind the iris and lens). The posterior eye includes the vitreous, retina, and choroid. The vitreous is the jelly-like substance that fills the back of the eye. The retina is a delicate nerve tissue that lines the back inside wall of the eye and is the part of the eye that converts light into an image that that is sent to the brain. The center of the retina is called the macula and this is where fine vision is located. The choroid is a highly vascular layer underneath the retina that nourishes it. Damage to the retina can cause permanent vision loss.

A retina specialist is a medical doctor trained as an ophthalmologist, who has received additional fellowship training in diseases and surgery of the vitreous and retina. Our Farmington and Glastonbury, Connecticut retina specialists commonly treat macular degeneration, diabetic retinopathy, vitreous hemorrhage, retinal tears, and retinal vein occlusions.

The examination at Consulting Ophthalmologists, P.C. will begin with an ophthalmic technician who will obtain your history and check your vision, eye pressure, and pupils. Then your eyes will be dilated.

A retina exam is focused on the back of the eye. For this reason, the doctor will spend a lot of time looking through your pupil at the vitreous, retina and other structures located inside the back portion of the eye. In order to adequately see the retina, every patient can expect to have their eyes dilated. The eyes take 20 to 40 minutes to fully dilate so you will generally be sitting in the waiting room after seeing the technician and before being taken into the doctor’s examination room. Often while you are dilating specialized tests, such as optical coherence tomography will be performed.

The following methods are normally used in diagnosing retina problems:

Upon completion of the tests required for an accurate diagnosis, the doctor will discuss the various treatment options. The entire retina examination generally will take from 1 ½ to 2 hours, especially if this is your first examination. Your eyes will remain dilated for 2 to 4 hours after the examination. During this time you will have blurred vision, especially at near, and be sensitive to light. It’s a good idea to bring sunglasses to wear for the trip home and if you feel uncomfortable driving, bring someone to drive you home.

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is a chronic condition that causes central vision loss. It affects millions of Americans. In fact, it is a leading cause of blindness in people 60 and older. The older you are, the greater your chance of being affected. AMD occurs when the macula—the central portion of the retina that is important for reading and color vision—becomes damaged. AMD is a single disease, but it can take 2 different forms: dry and wet.

Symptoms of AMD include blurriness, wavy lines, or a blind spot. You may also notice visual distortions such as straight lines or faces appearing wavy, doorways seeming crooked, or objects appearing smaller or farther away. If you notice any of these symptoms, you should see an ophthalmologist as soon as possible.

Dry AMD occurs when the light-sensitive cells in the macula slowly break down, gradually blurring central vision in the affected eye. As dry AMD gets worse, you may see a blurred spot in the center of your vision. Over time, as less of the macula functions, central vision is gradually lost in the affected eye. You may have difficulty recognizing faces. You may need more light for reading and other tasks. Dry AMD generally affects both eyes, but vision can be lost in one eye while the other eye seems unaffected.

Wet AMD is the more serious form, with more than 200,000 people in the United States diagnosed every year. Without treatment, patients can rapidly lose their central vision, leaving only peripheral, or side, vision. Wet AMD occurs when abnormal blood vessels start to grow under the macula. These new blood vessels tend to be very fragile and often leak blood and fluid.

Diabetic retinopathy is caused by damage to blood vessels of the retina. Diabetic retinopathy is the leading cause of blindness in working-age Americans. People with both type 1 diabetes and type 2 diabetes are at risk for this condition. Having more severe diabetes for a longer period of time increases the chance of getting retinopathy. Retinopathy is also more likely to occur earlier and be more severe if your diabetes has been poorly controlled. Almost everyone who has had diabetes for more than 30 years will show signs of diabetic retinopathy.

Nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy is the early and less severe form of diabetic retinal damage. Blood vessels in the eye become larger in certain spots (called microaneurysms). Blood vessels may also become blocked. There may be small amounts of bleeding (retinal hemorrhages), and fluid may leak into the retina (edema). This can lead to noticeable problems with your eyesight but early diabetic retinopathy usually causes no symptoms.

Proliferative diabetic retinopathy is the more advanced and severe form of diabetic retinal damage. New blood vessels start to grow in the eye, either from the retina or on the iris. These new vessels are fragile and can bleed (hemorrhage). Small scars develop, both on the retina and in other parts of the eye (the vitreous). The scars may cause retinal detachment. The end result is vision loss, often severe.

Macular edema develops when blood vessels in the retina are leaking fluids. The macula does not function properly when it is swollen. Vision loss may be mild to severe, but in many cases, your peripheral (side) vision remains. Macular edema is often a complication of diabetic retinopathy and is the most common form of vision loss for people with diabetes—particularly if it is left untreated. Eye surgery, including cataract surgery, can increase your risk of developing macular edema due to blood vessels becoming irritated and leaking fluids. Some of the other causes of macular edema age-related macular degeneration, uveitis, retinal vein occlusion, blockage in the small veins of the retina due to radiation or macular telangiectasis, side effects of certain medications, or certain genetic disorders, such as retinoschisis or retinitis pigmentosa.

The macula normally lies flat against the inside back surface of the eye. Sometimes cells can grow on the inside of the eye contracting and pulling on the macula. Occasionally, an injury or medical condition creates strands of scar tissue inside the eye. These are called epiretinal membranes, and they can pull on the macula. When this pulling makes the macula wrinkle, it is called macular pucker. In some eyes, this will have little effect on vision, but in others, it can be significant leading to distorted vision.

The vitreous fluid, the gel-like material that fills the eyeball, is attached to the retina around the back of the eye. If the vitreous changes shape, it may pull a piece of the retina with it, leaving a retinal tear. Once a retinal tear occurs, vitreous fluid may seep between the retina and the back wall of the eye, causing the retina to pull away. This results in a retinal detachment.

Retinal detachment is the separation of the retina from the tissues under it. A retinal detachment caused by a tear or a hole in the eye is the most common type. This type, if not treated, will cause blindness. If your central vision is still good, it is important to promptly treat the detachment with surgery to save your vision. If your central vision is worsened by the detachment, it usually means that the retina has detached through the center portion (the macula). If your retina has already detached through the macula, the surgery is not quite as urgent.

Floaters are little “cobwebs” or specks that float about in your field of vision. They are small, dark, shadowy shapes that can look like spots, thread-like strands, or squiggly lines. They move as your eyes move and seem to dart away when you try to look at them directly. They do not follow your eye movements precisely and usually drift when your eyes stop moving. Most people have floaters and learn to ignore them; they are usually not noticed until they become numerous or more prominent. Floaters can become apparent when looking at something bright, such as white paper or a blue sky. Floaters occur when the vitreous, a gel-like substance that fills about 80 percent of the eye and helps it maintain a round shape, slowly liquifies. In most cases, floaters are part of the natural aging process and simply an annoyance. They can be distracting at first, but eventually tend to “settle” at the bottom of the eye, becoming less bothersome. However, there are other, more serious causes of floaters, including infection, inflammation (uveitis), hemorrhaging, retinal tears, and injury to the eye.

The vitreous is the clear gel that fills the central cavity of the eye. It occupies approximately 80% of the volume of the eyeball and is formed by a network of collagen fibrils and macromolecules of hyaluronic acid. The formed vitreous gel liquefies with age and eventually separates from the retina. This event is called a posterior vitreous detachment (PVD) and is a normal event occurring in most people sometime between 50–70 years of age. A PVD will often occur at an earlier age in people who are nearsighted or have undergone cataract surgery.

For more information from the American Society of Retinal Specialists click here.

499 Farmington Avenue, Suite 100

Farmington, CT 06032

Office Telephone: 860-678-0202

295 Western Boulevard

Glastonbury, CT 06033

Office Telephone: 860-678-0202